Cranial Cruciate Ligament Rupture: The ACL of the Pet World

The Scenario

"Honey Bee is limping again. What should we do?" "Oh, give her a couple of aspirin, and she'll walk it off."

So here you are, sitting in your veterinarian's office because Honey Bee has not improved. You may also have noticed the slight eye twitch the vet developed while you recounted the tale of the mysterious limp.

Lameness is one of the most common sick visits we see. Knowing what to tell your vet will make the process much easier (and hopefully cheaper). While there are many causes—like fractures or soft tissue injuries—today we are focusing on the big one: the Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL).

3 Rules Before We Begin

The most important lessons from this article:

No Dr. Google: Never use online resources to diagnose or treat a disease.

No Home Pharmacy: Do not give your pet medication without consulting a veterinarian first.

Seriously:

"Do not. Give your pet. Medication. Without consulting. A veterinarian first."

Why? Worst case: You seriously injure your pet or delay life-saving treatment. Best case: We will judge you. Heavily.

The Anatomy: What is a CCL?

Cranial Cruciate Ligament runs from the back of the femur to the front of the tibia.

The Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL) is the animal equivalent of the ACL in humans. Its job is to stabilize the knee by attaching the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone).

The "Soccer Player" Analogy: Imagine you plant your leg to kick a ball, and someone hits you from the side. (how I tore my ACL the first time)

The Femur moves one way.

The Tibia stays put.

The Knee gives up.

And your parents' bank account screams. (Sorry, Mom and Dad).

Unless Honey Bee is secretly Air Bud, she probably wasn't playing soccer. But if she is overweight and chases a squirrel, the result is the same: pop.

The Process: From Limp to Diagnosis

When the CCL ruptures, the knee becomes unstable.

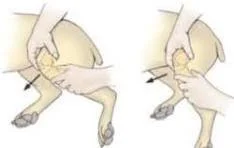

The Exam: We manipulate the knee to feel for a specific "drawer motion" (instability). Since this hurts, we often need sedation to do it safely.

X-Rays: These help us rule out fractures or bone cancer and confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment Options

Now that we know it's ruptured, you generally have two paths:

Surgery (Recommended): We stabilize the knee by altering the bone geometry or using a high-strength suture. This offers the best chance at a pain-free life.

Medical Management: We use long-term pain meds and rest.

Warning: This is rarely recommended for active dogs because arthritis and reinjury are almost guaranteed.

Recovery & Prevention

1. Weight Management Keeping your pet at a healthy weight is the #1 way to prevent this.

Note: If one knee blows, the other is at high risk—especially if the dog is overweight.

Read More: Check out my guide on Your Pet’s Diet.

2. Activity Restriction Just like with humans, rest is critical. If you let them run too soon, the surgery will fail.

3. Pain Medications We can use meds to help, but never mix them without asking us.

Mixing NSAIDs (like Rimadyl) with steroids or aspirin can cause severe, bloody stomach ulcers.